Maoism Resurgent: The Cultural Revolution has Come to the West

Surajreet Singh, Print Editor-in-Chief

October 8, 2020

A special opinion piece by our Print Editor-in-Chief.

As the world reeled from the shocking footage of George Floyd’s murder, there was a chance to unite two Americas. People across the political spectrum decried the actions of Derek Chauvin and for once, there were indications that the country could finally institute proper reform.

However, something else began appearing. As peaceful protests erupted across the United States to support black lives, there was a simultaneous movement to rail against the institutions of power, calling for the overthrow of the elites and the toppling of the capitalist system. A new Cultural Revolution began in earnest. Statues were toppled, places were renamed, people were shamed online and in public for their opinions, and innocents were persecuted by violent mobs, who believed their enemies were within the nation. Aspects of Maoism have infiltrated the West and China can only sit back in bemusement. They have seen this all before.

The Mandate of Heaven

The original iteration of the Cultural Revolution in Chinese characters offers insight into Mao’s own thinking. 文化 大 革命 is the name given for “The Great Cultural Revolution” and it is the last portion of the phrase that bears the most weight, translating to “a change in destiny in accordance to the Mandate of Heaven”. The movement was seemingly enshrined in divinity, offering purpose to those who joined. The revolution began with the May 16th Notification in mid-1966, a document written under Mao’s supervision that implied that the enemies of the Communist cause had infected the party itself. Following the purge of Beijing mayor Peng Zhen, chaos ensued and a call to arms occurred.

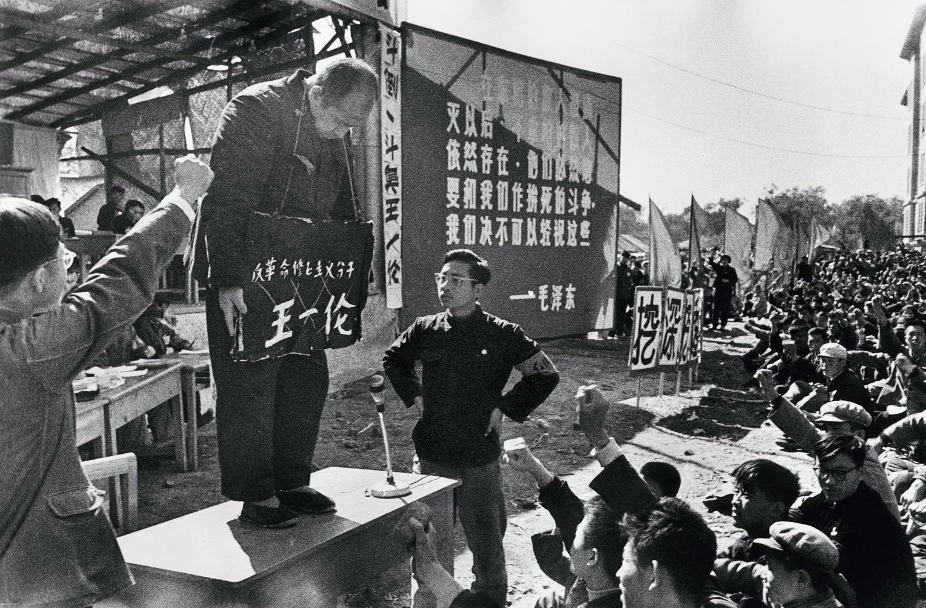

The mobilization started with the students, who began rebelling against their educational establishments and taking to the streets demanding an overthrow of the system while blazoning Mao’s portrait. The Red Guard acted as the vanguard, as prominent revolutionary Lin Biao called for the destruction of the “Four Olds”: customs, culture, habits and ideas. The publication of pieces from “The Little Red Book” revealed Mao’s intentions: “to transform education, literature and art, and all other parts of the superstructure that do not correspond to the socialist economic base, so as to facilitate the consolidation and development of the socialist system.” Following its release, the revolutionary spirit spread across China, growing increasingly violent as city streets, places and even people were targeted. Public humiliations, known as struggle sessions, were a tactic used by the Maoists, where groups would gang up on public figures and engage in physical and verbal abuse towards them. The aim was to forcefully induce confessions of guilt for “crimes against the Party.” Many who observed such things indicated that those with above average skills, no matter how slight, were targeted in these sessions. Joined by the military and law enforcement and following the deaths of up to two million people, Mao completed the transformation of the country and cemented his status as the founding father of the People’s Republic of China, who have cherished him ever since.

Maoism in the West

Mao’s teachings are certainly being seen today. His stated goal in “The Little Red Book” is being witnessed today: in the universities. Jonathan Haidt, a psychologist renowned for his work in explaining the different mindsets in liberals and conservatives, has long warned about the growing political polarization and the change in culture at universities. In his book “The Coddling of the American Mind”, Haidt and his colleague Greg Lukianoff argue that the proliferation of three “great untruths”, namely “what doesn’t kill you makes you weaker”, “always trust your feelings”, and “life is a battle between good people and evil people”, have set the stage for political absolutism on college campuses. By holding sacred the ideas of intersectionality, microaggressions, trigger warnings and other like terms, Haidt contends that a generation has been set up for failure, instilled with a mindset towards “safetyism”, the acceptance of revisionist history, and the belief that institutions that did not guarantee equitable outcomes must be intrinsically inequitable. These changes began to spread from college campuses into the rest of the country.

As many entering the workforce adopted this line of thought, key public institutions began to be compromised in the United States in an eerily familiar fashion to the Maoist movements all those years ago. U.S. Senator Tom Cotton’s opinion piece calling for military action to end the protests across the country had instead spurred a war within the New York Times. Journalists of colour within the organization began tweeting about the danger the piece had posed to their lives, despite the fact that Senator Cotton’s work had laid out a legal and historical case for military action. The Times was a paper of superlative standing, having been a bastion of journalism since its inception in 1851 and offering voices even to those fundamentally opposed to traditional Western values, such as Russian president Vladimir Putin and the Taliban. In the end, they submitted. The editorial editor resigned and the words of an elected American official were removed.

It has not stopped there. Stores in major cities were looted, buildings defaced, public officials figuratively guillotined for supporting law enforcement and across the country, ordinary citizens found themselves faced down by mobs demanding allegiance. All of this was framed as a movement of the people against corrupt and broken institutions, vowing their ultimate collapse. The extreme ends of the political spectrum had risen, joining in the new class war. It was farcical that major media organizations across the United States insisted that these things were not happening. They have told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. Oceania was at war with Eastasia, they’ve always been at war with Eastasia.

The Future Ahead

While the West will undoubtedly overcome this moment, it is of utmost importance for us to recognize that the de-platforming, canceling or suppression of ideas that do not adhere to our world view is the antithesis of the values of the democratic societies we live in. This has been recognized by many prominent intellectuals such as Noam Chomsky, Steven Pinker and Yascha Mounk, who have signed onto “A Letter for Open Justice and Debate” arguing “The democratic inclusion we want can be achieved only if we speak out against the intolerant climate that has set in on all sides.”

For those views that society deems abhorrent, it is up to society to disprove those very views. This has worked in the past. In 2009, the BBC segment “Question Time” invited Nick Griffin, leader of the far-right British National Party, onto their program to answer questions from the audience. Under heavy fire from the audience and many fellow guests, Griffin wilted and, after the show, sought to cast the media apparatus as biased against him. However, despite polls of viewers claiming they would consider the BNP in future elections, the party was swept from almost all political positions within the United Kingdom just a year later. Voters stepped up and fought back against political extremism. We must do the same now.